For years, scientists believed that differences in primate and human brains explained why only humans can produce meaningful sounds.

However, Axel Ekström, a phonetician and cognitive scientist from the KTH Royal Institute of Technology, and his colleagues are challenging this belief.

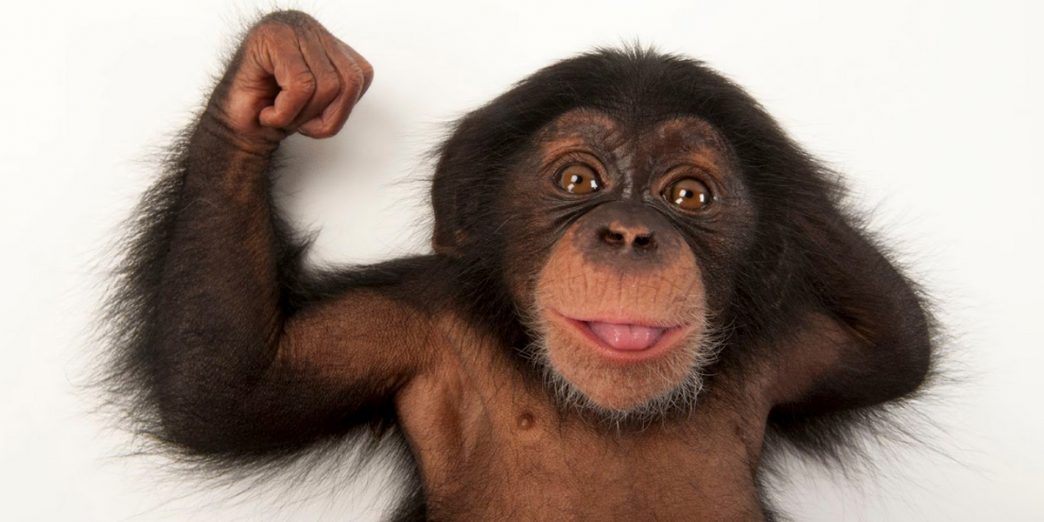

By examining home videos and a 1960s newsreel featuring two chimpanzees, they propose that the presumed barrier preventing chimpanzees from coordinating their jaw and voice may not exist.

One video featured Johnny, a chimpanzee from the Suncoast Primate Sanctuary in Florida. According to the video owner, Johnny used the word “Mama” to get what he wanted.

Watch the video:

“Mama” might have been one of the first words in human language

In their study, Ekström and his team discovered two unrelated chimpanzees on different continents vocalizing what sounds like “mama,” a word they were reportedly taught by their English-speaking caregivers.

The researchers note that “mama” might have been one of the first words in human language.

The ‘m’ sound is common in human languages and is often among the first sounds babies make, making the ‘m-vowel-m’ pattern relatively simple to produce.

“Papa” and “Cup”

Ekström’s earlier research included analyzing a 1960s recording of a third chimp saying ‘papa’ and ‘cup.’ These findings suggest that chimpanzee brains can intentionally mimic some sounds they hear, supporting the idea that great apes can learn vocal production.

In the wild, chimpanzees primarily use gestures for communication but do use various vocalizations.

Their gesture-based communication is structured similarly to human vocal language. Gibbons, another primate, can produce over 20 distinct sounds with different meanings.

Past reports of primate speech were often dismissed due to a lack of rigorous analysis. However, Ekström and his team argue that a lack of evidence is not the same as evidence of absence. They believe earlier studies were flawed due to unethical conditions that skewed the results.

The great ape language projects from 50 years ago often involved social isolation and neglect, which did not allow these intelligent primates to display their true abilities.

Avoiding anthropomorphism in animal studies sometimes led to underestimating animal intelligence. Just as science progresses in steps, human intelligence builds on pre-existing foundations.

Ekström and his colleagues conclude that “great apes can produce human words,” and that previous failures to demonstrate this were due to flawed research methods, not the animals’ capabilities.

This research was published in Scientific Reports.